For me, living well in Mexico includes regularly enjoying the country’s diverse cultural heritage and vibrant art scenes. You can often find me wasting hours in one of Mexico City’s world-class museums, aimlessly strolling through artisan workshops, or contemplating the history behind Guadalajara’s politically charged 20th-century murals.

Most Mexicans take great pride in these artistic riches, too. And it’s why I was stunned to learn that some of Mexico’s most prized fine art has disappeared in recent years, with virtually no media coverage beyond the art world.

No idea what I’m talking about?

I’m referring to the alleged theft of multiple items from the Frida Kahlo museum in CDMX, better known as Casa Azul (Blue house).

If you haven’t heard about it, I’m not surprised. Unlike the high-profile heist at the Louvre last month, these Mexican works disappeared with no knowledge or fanfare.

Below, I share the sordid story that few in Mexico want to talk about.

Frida Kahlo’s Works That Disappeared from Casa Azul

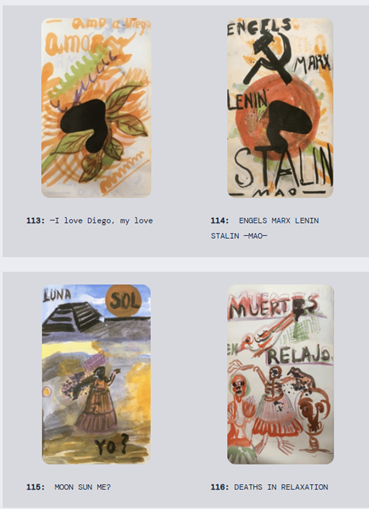

According to the former director of the Museo Frida Kahlo, a woman by the name of Hilda Trujillo Soto, two oil paintings, 8 drawings, and 6 two-sided diary pages of Kahlo’s disappeared from the Casa Azul inventory between the initial inventory catalogued by Diego Rivera in 1957 and the second inventory completed in 2011.

These include:

- Congress of Peoples for Peace, painted in 1952.

- Frida in Flames (or Self-portrait inside a Sunflower), painted in 1954.

- Eight drawings by Frida are missing, including American Liberty and My Bedpan Doesn’t Love Me Anymore.

- Six double-sided pages from Frida Kahlo’s diary that contained mostly drawings.

The location of some of these artworks is known.

Congress of Peoples for Peace was sold for $2.66 million in June 2020 by Sotheby’s New York, when much of the non-essential U.S. economy was shut down, to an anonymous private collector.

Credit: Markus Schrieber/AP.

Frida in Flames (also sometimes referred to as Self-portrait inside a Sunflower) was sold in December 2021, at a time when the COVID-19 pandemic embattled Mexico. The New York-based Mary-Anne Martin Fine Art Gallery auctioned this work, listing the painting’s provenance as “Private Collection, Dallas.” An anonymous private collector purchased this painting as well.

Credit: Cindy Ord/Getty

The current location(s) of the various drawings and missing diary pages are unknown, but Trujillo believes they were removed from the original during a period when it had been moved from public display to a storage safe at Casa Azul back in the 1990s.

Credit: Hilda Trujillo blog.

The Vast Art Collection by Frida and Diego That The Mexican Government Oversees

Diego and Frida’s artistic legacy included their own original works, as well as pre-Hispanic art collected fanatically by Diego throughout his adult life and the couple’s personal effects. This includes a vast array of books, jewelry, painting tools, clothing, photos, diaries, and more.

The works of art by Frida and Diego and their personal effects were gifted to the people of Mexico by Rivera in 1957. It was a legally binding agreement through an irrevocable Trust (fideicomiso), with documents notarized and signed by Rivera and officials at the Bank of Mexico.

This gave the collection special protections under Mexico’s natural heritage laws. Under the agreement, Rivera also stipulated that the works never be removed from the properties of Casa Azul and the Anahuacalli Museum (or from Mexico), not even for exhibitions at other museums.

Hilda Trujillo’s Lonely Crusade to Recover the Lost Art

Trujillo brought accusations about the missing works public last April. She published a meticulously detailed blog post (you can read it here) describing what disappeared and who was in a position to know what happened.

To summarize her claim, an internal audit at Casa Azul in 2011 revealed inconsistencies in the original inventory of Kahlo’s works documented by Diego Rivera in 1957 when compared to the museum’s current collection. This study highlighted the missing works listed above, among others.

The 2011 audit, commissioned by Carlos Phillips, involved numerous unnamed collaborators.

For background, Carlos Phillips Olmedo was the son of the wealthy art collector and original director of the Museo Frida Kahlo, Dolores Olmedo. Philipps had succeeded his mother as director of the Kahlo & Rivera museums as well as her own museum, following her death in 2002.

Dolores Olmedo was not only an art patron but a close friend of Rivera’s who became the executor of his and Kahlo’s estates after Rivera died in 1957 (Frida died in 1954). Olmedo continued in those roles for more than 40 years.

If you reach the end of Trujillo’s blog post, she insinuates that personal animosity between Dolores Olmedo and Frida Kahlo may have played a role in the disappearances, given her long tenure as museum director with minimal (if any) oversight by the Bank of Mexico trustees.

With regard to the missing pieces, Carlos Phillips had no explanation. Trujillo says she became aware of the report’s findings in 2013 and never set eyes on the original document.

Trujillo urged Phillips to file a formal report with CONACULTA (the Ministry of Culture) and INBAL (National Institute of Fine Arts and Literature) to declare the works missing. Phillips told her he’d share the report’s findings with the general trustee José Luis Pérez Arredondo at the Bank of Mexico, the Attorney General’s office, and the INBAL.

Trujillo doesn’t know if he actually did. What we do know is that nothing happened.

The missing Kahlo works have since been reclassified by the museum as being in private collections, with no explanation as to how they left Casa Azul. This outcome could be one of two things — extreme embarrassment or blatant corruption.

Trujillo’s isn’t simply a lone voice in the wilderness.

Her claim has been backed by several renowned art historians specializing in the works of Frida Kahlo. This includes Helga Prignitz-Poda, a German art historian who co-authored a comprehensive catalog of all known artworks by Frida Kahlo, the catalog raisonné.

The Mexican Government’s Response

This is where things get even more interesting.

Following the publication of Trujillo’s blog post in April 2025, art media around the world began covering the story of Frida’s disappeared art. But the Mexican government dismisses Trujillo’s claim that art was illegally taken from Casa Azul, saying they were nothing more than the rantings of a disgruntled ex-employee.

Rather than investigate, the government has chosen to hide behind bureaucratic excuses, stating they couldn’t do anything because Trujillo never filed a formal report about missing art. This would imply that Carlos Phillips never shared the findings of his 2011 study with government officials — or someone was covering it up.

Then INBAL issued a press release stating it has “not granted any permits” for the permanent export of works by Rivera or Kahlo. This means the paintings were exported without licenses, which frankly isn’t easy to do when they’re this famous. INBAL inadvertently confirmed foul play.

It’s a baffling situation. Even casual followers of the art world know that both AMLO and President Sheinbaum have zealously pursued the recovery of pre-Hispanic works of art illegally trafficked to collectors abroad.

Plus, the Frida paintings in question were openly sold by well-known foreign auction houses. They hadn’t disappeared into thin air.

Trujillo thinks her gender may be to blame. She believes that if her accusations had been brought by a man, they would have been taken more seriously.

While chauvinism is an entrenched problem in Mexico, I think it’s about the money.

In recent decades, Kahlo’s become one of the country’s foremost cultural exports, a posthumous ambassador for all that is mysterious, passionate, sensual, decadent, and fiercely Mexican. Her works are selling for truly mind-boggling sums.

In this context, Trujillo’s accusations are more than a little embarrassing for the government tasked with safeguarding her art.

A Real Whodunnit

It’s been 14 years since Casa Azul staff discovered gaps in the collection Diego Rivera bequeathed to the state in 1957. And we’re still no closer to knowing…

Who removed these works from Casa Azul, and when? How much money was pocketed, and by whom?

Is the government protecting well-connected insiders who personally profited from theft?

A Kahlo painting sold last month set a record for the highest price ever paid for a work of art from Latin America, by a man or woman. El sueño (La cama) fetched an astonishing $54.7 million USD. (once again, Sotheby’s New York handled the sale) It topped the record set in 2021 of $34.9 million from the sale of Frida’s painting, Diego y yo.

With sums like these involved, it may be the best explanation we’re going to get for why no one in power wants to investigate. But the Mexican people deserve better.

Sources: Hilda Trujillo’s blog, The Guardian, and The Art Newspaper